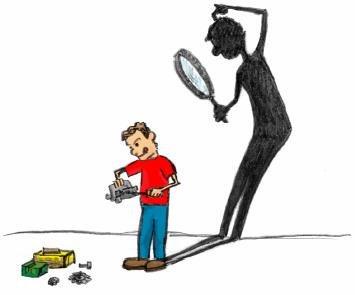

Me and My Shadow

Identify Your Customers’ Hidden Needs

Designers have a wealth of ideas on how their products can and should be used. These idealized notions keep competitors and quality assurance people in business, as designers never seem to include the idea that a cell phone makes a great door stop, or that a remote controlled toy dump truck is the best way to move your keys, wallet, and the TV remote control across the room after you’ve had knee surgery, or that the best way to soothe a crying baby is to put them on top of the washer or dryer. Of course, few of your customers will remember to tell you about these experiences. To learn about them, you need to watch your customers use your product on their terms, not yours.

-

Shadow your customers while they use your product or service. Literally. Sit or stand next to them and watch what they do. Periodically ask them, “Why are you doing that?” and “What are you thinking?” Take along a camera and make photos of key activities and the context in which work is accomplished. Ask for copies of important artifacts created or used by your customers while they are doing the work. Bring along other customers and use them as interpreters to explain what a customer is doing, help you ask clarifying questions as to why the customer is doing things this way. During the game, ask your other customers to share whether they dothings the same way with the person you’re observing, and watch how your customers explore and even debate the various approaches they bring to using your products and services.

Me and My Shadow differs from The Apprentice in that Me and My Shadow focuses on observation and The Apprentice focuses on experience. Click here to understand other characteristics of the game.

-

This technique is one of many that falls under the broad category of ethnographic research. Ethnographic research is an incredibly powerful way of understanding your customer, but it comes with a catch: it is hard to observe your customer in such a way that your observations don’t change how they work. It’s kind of like the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle applied to people instead of quantum particles. That’s why the name of this game emphasizes thinking of yourself as a shadow, so that you can minimize any negative interactions caused by your observations.

Sophisticated applications of this technique are based on specially selected customers being asked to perform activities while being studied in specially constructed observation rooms. Although this can be an extraordinary way to uncover hidden requirements, the process is both expensive because of the special room charges and time consuming, and the setting tends to be artificial. Me and My Shadow works best when you can observe your customers in their native habitat (with native guides in tow).

-

Consider the working context of your customer in preparing for this game. You may need special preparations or approvals because of safety, privacy, security, or related factors. Addressing these items early in the planning process will make certain that you have time to handle all the necessary details before playing the game. A detailed examination of these factors is beyond the scope of this book because laws governing this behavior vary considerably by country.

This game often takes longer than other games. Depending on the location of your customers and the factors mentioned above, it may also cost more money.

Me and My Shadow can be used anytime, but you’ll obtain the best results when you try this technique on nontraditional customer segments. To illustrate, consider segmenting your customers by experience: new customers, customers who have used your product for one month, six months, and one year or more. Alternatively, try segmenting your customers based on perceived motivation: those who want to use your product, those who are indifferent about using your product, and those who don’t want to use your product but cannot find or justify an alternative, and in rare cases, those who may be forced to use your product. Although you may not be able to change their motivation for using your product, you will find that you develop different insights from each group.

Although you’ll try your best to miss nothing, chances are pretty good that you’ll miss a lot of things. That’s understandable, because there is often so much to see that it is hard to know what to observe. Do the best that you can and don’t expect that to be perfect. Take comfort in the knowledge that making the commitment to develop customer understanding using these games will put you ahead of your competition.

As you prepare to play the game, consider exactly who will join you at the customer site. You probably won’t need a helper or a facilitator. You will still need observers and a photographer. Inquire about any security policies because you may have to obtain special badges or access permissions for your team. You may also need special permission to bring along cameras.

-

Arrive early and be respectful of the cultural norms of your customers, including the way that they dress. Don’t force them to immediately use your product. Instead, establish a rapport and let your customer control the pace at which the visit unfolds. You’ll get your chance to observe your customer. Honor all requests to stop making observations or to leave the room, especially when concern or fear is expressed (“You’re not going to tell my boss that I’m not sure how to operate all features of this machine, are you?”).

In most Innovation Games, observers record observations on 5"38" cards, one observation per card. In this game it is better to bring along a simple notepad or notebook and jot down the details you think are nec essary. I prefer unlined paper so that I can make quick sketches. Others prefer graph paper. As you make your observations, record the time, location, and customers involved. If it helps, bring along a voice recorder and record your observations.

As soon as you finish with your customer, find a private location and immediately write down everything that you can remember. The longer you delay, the more that you risk forgetting. While you’re recording your observations, try to avoid making evaluations. That comes later, during the normal phase of observer note processing. In this phase you should simply focus on your perceptions and observations.

Here are some of the things you may want to capture in your observations:

The people who interact with your customer.

The products and services that they use at the same time they are using your products or services.

Utterances, body language, or facial expressions that give insight into their emotions as they use your products or services.

The physical environment and larger context of their workspace.

Your own feelings and reactions to what is going on.

-

Organize a meeting of everyone who visited or observed customers. It is best if everyone can attend this meeting in person (not a teleconference). Hand each person a stack of 5"38" note cards and masking tape or large sticky notes and ask them to transcribe their observations onto these cards, one per card. When they have finished, ask them to tape each card to the wall. Review each observation, grouping them into meaningful patterns. Discuss the patterns, capturing any meta-observations (observations about the patterns and/or the observations) as new observations. Next, do the following:

Transcribe all observations into a spreadsheet, with one observation in each row.

Assess each observation along the following dimensions:

Novelty—The degree to which the observation indicates a novel or unintended use of the product.

Performance gap—The degree to which the observation indicates a performance gap between desired and actual performance. Large gaps mean large problems.

New opportunity—The degree to which the observation indicates a new opportunity for solving a customer problem.

For example, suppose you make various tools for home gardening and you decide to watch how home gardeners use these tools. You might observe that a home gardener forms a "pouch" with their shirt to hold vegetables they pick from their garden. If you or your team have never seen this before, you might rank it as highly novel, with no relationship to your existing tools, and a strong new opportunity for a new solution that would help gardeners hold the vegetables that they pick (like a special gardening shirt with big pouches).

-

Notepads or notebooks

Recording devices appropriate to the task at hand as approved by your customer

-

One of the most successful and celebrated programs of ethnographic research is Intuit’s “Follow-Me- Home” program, in which employees follow Intuit’s customers to their homes, places of work, and other locations in which they use Intuit products and services. This program has been credited with several breakthroughs, including substantial improvements to Quicken and QuickBooks as well as new QuickBase. It is a cost effective and efficient way to gain the understanding you need to create true innovations.

Me and My Shadow shares the same core operating principle as Intuit’s Follow-Me-Home: ethnographic observation, with the addition of bringing along another customer who acts as a guide or subject matter expert. This is especially important in B2B and B2P environments, when the creators of the product may not be the experts in its use.

-

You may think that capturing participants on a video camera for subsequent review is the best way to play this game. Although a record of behavior can be compelling, I recommend against this for a variety of reasons:

Observers tend to become sloppy in their observations when they think they can go back and watch a video tape.

Unlike the role of the Bad Wedding Photographer, in which lots of photos take the place of a few high quality photos, video needs to be more professionally obtained. The need for greater degrees of professionalism (that is, making certain the camera isn't jiggled, providing adequate light, ensuring that audio levels are correct, and so forth) substantially increases costs.

The professional aspect of the video tends to highlight the fact that participants are being watched, which often causes them to change their behavior. This can be contrasted with the Bad Wedding Photographer, as many times participants forget that they're being photographed (especially when a lot of photographs are taken and they are not asked to pose for the camera).

There are often complex legal issues associated with videotaping subjects, especially in Europe, and EMEA.

It takes between 5 and 10 hours (and some say longer) to review one hour of video. In other words, video review is a slow, expensive process. More importantly, in many cases it does not produce a materially better result than recording your impressions in real time and then reviewing your results as a team.

Whereas videotaping customers usually creates more problems than it is worth, carefully selected photographs can be your best friend. By focusing on the results of the work, you can record the most essential elements of the work and avoid many, if not all, of the issues (especially legal issues). If you really think that video is superior to photographs, consider that in the real estate market, prospective buyers tend to prefer a few well-chosen photos (which just about anyone can take with high quality) to a video walkthrough.

There are times when even I will concede that a video record is the most powerful way of communicating your observations. A skeptical product team who just can’t believe that their product is hard to use can be convinced a redesign is required when they observe customers struggling to accomplish basic tasks. If you feel that you simply must use video to accomplish your goals, then do so, but keep in mind the potential land mines discussed earlier.